By Mikhailo Minakov*

Today’s protests in Belarus provoke great interest and solidarity in European societies, both in West and East of the continent. But this significance is symptomatic in two different ways: for the Western European nations, it nostalgically reminds about sociocultural optimism of 1990ies when the project of European Union made such strong leap into the future. And for the Eastern European autocracies Belarusian protests present a very strong destabilizing factor.

Contemporary Belarus is a classical post-Soviet country where elements of late Soviet cultural legacy is combined with new Eastern European experience. In 1991 Soviet peoples, including Belarusians, have made a choice in favor of pluralist democracy, market economy, and ethnonational revival. For late Soviet Perestroika generations, these three ideas were seen as a way to change Soviet Union into a more free and more inclusive society and a richer economy. Since the new Union Treaty was not signed due to the coup d’état in August 1991, the nation-state agenda became dominant and the Union was dissolved.

For the Belarus population in early 1990ies, the change meant rapid nationalist cultural reforms, economic crisis, and poverty. As a reaction to these changes, a young neosovietist populist has won the presidential elections in 1994-1995.

In those times, political scholars, who firmly believed into transition theory predicting post-Soviet democratization, assessed the Belarussian emerging authoritarian regime as a deviation of common European mainstream and “the last European dictatorship”. But in today’s perspective, it was the first dictatorship opening an era of authoritarian creativity of the post-Soviet elites repeated in Southern Caucasus, Eastern Europe, and Russia.

The Lukashenko regime was among the most stable non-free regimes in the region. On one side, it produced very strong state institutions, government-controlled media and industry, vibrant small business, and much more socially oriented socioeconomic development then in Russia or Ukraine. The GDP per capita in fixed prices doubled in 2019 in comparison to 1991. In 2019, for example, Ukraine and Moldova were still around the same GDP per capita figures as in 1991. Belarus was the only out of six Eastern Neighborhood without territorial problems. Lukashenko successfully balanced between West and putinist Russia to defend his regimes’ autonomy and economic success.

On the other hand, the Belarus regime did not give the room for existence of the free media, education, civil society, and opposition parties. Political liberties and civic freedoms were severely suppressed. The best Belarussian universities had to emigrate to Lithuania in early 2000. Belarussian state was controlled by autocratic personalist pyramid serving to Aleksander Lukashenko for over 26 years.

The Lukashenko regime had its crises. The big protest waves and repressions against their participants took place in 2006 and 2010. In 2015, anticipating Russian imperialist meddling and Ukrainian revolutionary influence, Lukashenko organized early presidential elections, cleansed pro-Russian and pro-Western NGOs, and purged security services and military. He was easily reelected, while attempts of protests were easily suppressed.

But around 2017-2020 all aged post-Soviet autocracies started preparing for transition of power. Russia and Kazakhstan started their own preparations. But Lukashenko failed to recognize the problem — also strengthened by his denial of COVID-19 epidemic and growing socioeconomic problems — and tried to repeat usual re-election in 2020.

The protests that started in August 2020 turned out to be unprecedented for Belarus. They involve a huge number of citizens from all social strata and generations. They are spread in the capital and in provincial towns. And the regime does not find the effective way to suppress the protest and restore the usual order.

These protests have commonalities with other Eastern European nations — Moldova (2009, 2015, 2018), Ukraine (Orange Revolution of 2004, and Euromaidan of 2013-2014), Georgia (Rose Revolution of 2003), or even Russian protests on Bolotnaia (2011-2013).

First of all, all post-Soviet societies ascribe special value to the honest elections and citizens. Elections have a strong moral significance for the citizens to recognize political legitimacy of elites. If elections are openly falsified, citizens have an urge to protest and get solidarized by strong civil spirit. This civil spirit is connected to political culture rooted in Perestroika experience. This solidarity is stronger than partisan differences. And the unity of protests is consolidated by delegitimized authoritarian figure.

Also, the common feature of the Belarus protests and other post-Soviet protest movements is the role of contemporary media. Orange Revolution in Ukraine was connected with the web-site of Ukrainska Pravda and TV Chanel 5. Twitter played a special role in Moldova protests, in Ukrainian Euromaidan the Facebook had a special value. And the Telegram channels of Nexta are significant for the communication of protesters in Belarus.

One more common feature is the importance of foreign recognition of the opposition as a legitimate force. The Belarusian opposition leaders are either arrested or emigrated to Lithuania and Poland. Western government are heavily involved into the support of opposition.

But the Belarus protests have unique features that separate the Belarus case from other revolutionary situations in post-Soviet region.

First of all, they are connected with the “tactics of water”. The protests do not take place on one city space where protesters would fight with security forces. Instead, protests take place around capital and country wherever possible.

Second, the Belarusian protests remain peaceful for very long time — for about 130 days now. The radicalization is very slow and limited [1]. Political leaders and intellectuals have adhered to the practice of peaceful resistance. The role of radical groups is almost invisible. Police provocations for a bloodshed and mass arrests remain unanswered. Protesters do not take over public offices or government institutions. This all sums up into permanent peaceful pressure on the authorities.

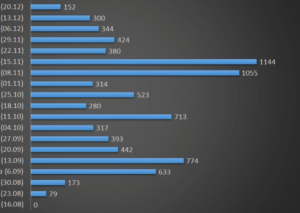

Graph: Number of arrested protesters in Belarus (August – December 2020)

Source: counts provided by Genadz Korshunau, ex-director of Belarus Institute of Sociology, source.

There is also a very different role of political parties. In Ukraine, Russia, and Moldova, parties were also trying to offer a political solution to protests. In Belarus party system is close to non-existence. For this reason, the protests’ leadership is changeable, but also protests do not have clear political agenda. Lukashenko rules through loyal bureaucracy that has not parties within it. Having no party relations, the Belarus protest reminds more Soviet social movements rather than post-Soviet ones.

Belarusian civil society is badly institutionalized. But the long existing civic organizations are controlled by government. This is why the protests are decentralized and are connected to new grass-roots civic initiatives. Repressions against leaders do not stop protests from happening. Emigrated Tikhanovskaia and imprisoned Kolesnikova are indeed the consolidating figures. But they are symbols, not political leaders that guide the revolutionary attempts.

In Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova local security services were too corrupt and weak to effectively suppress protests. In Belarus KGB is very strong, united and loyal to president, which undermines the possibility of political solution to the crisis.

Finally, the Russian factor is very different in Belarus. In Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova, the protests were connected to the conflict of Russia with the West and post-Soviet national elites. But in Belarus, Russophone elites are divided. Part of them support opposition. Very big part of Russophone society supports protesters. And even those who support Lukashenko do it against their repulsion to him. Also big part of protesters are oriented towards Russia (although their number dropped from 51% in September 2020 to 40% in November, while sympathies to EU have grown from 26% to 33% in the same period).

Having all these features of the Belarus protests in mind, the near future of Belarus will most probably be connected with a continuation of the crisis. Since the economic and epidemic situation continues to worsen, the protests will most probably continue. Their intensity in capital may drop down, but they will become stronger in the provincial towns.

Lukashenko will not be able to rule as before August 2020. His regime must become much more repressive and much less legitimate.

Opposition groups in Poland and Lithuania will stand by to return to the country when opportunity comes. These groups will most probably provide new president and ministers in the post-Lukashenko period.

Belarus is now in an open conflict with EU, Poland, Lithuania, and Ukraine. It cannot return to its previous effective international trade as before August 2020. Thus economic normalization will not happen anytime soon.

The constitutional reform, with strong impact of Russophone and Belarussian bureaucracy, may offer political resolution to the crisis. But lack of disloyal intellectuals and pro-Western opposition involvement makes the reform too illegitimate.

Destabilization of the Eastern European authoritarian belt started in Belarus. Lukashenko regime is a weak link in this authoritarian belt which may have a destabilizing impact on other autocracies in Eastern Europe.

Notes:

- Please see analysis (in Russian) of the protest trajectory and peace quality by Genadz Korshunau at source.

*Mykhailo Minakov. Senior Advisor, Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (https://www.wilsoncenter.org/person/mykhailo-minakov). Editor-in-chief of Kennan Focus Ukraine (http://www.kennan-focusukraine.org/), of Ideology and Politics Journal (ideopol.org), and of Koine.Community (https://www.koine.community/). Associate Fellow, Institute for European Studies, Europa-Universitaet Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder).

Tutte le ultime news dal mondo.

Tutte le ultime news dal mondo.